Pathological DEMAND AVOIDANCE

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance?

Pathological demand avoidance (PDA) is increasingly, but not universally, accepted as a behaviour profile that is seen in some individuals on the autism spectrum. People with a demand avoidant profile share difficulties with others on the autism spectrum in social communication, social interaction and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours, activities or interests (Autism.org.uk 2019). The Autism society (2019) suggests that “demand avoidance can be seen in the development of many children, including others on the autism spectrum. It is the extent and extreme nature of this avoidance that causes such difficulties, which is why it has been described as ‘pathological’.” Individuals with PDA need distinctive measures of help depending upon how severe their condition and levels of anxiety, and these individuals may need additional support as they move into adulthood.

The term Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome (PDA) was first used during the 1980’s by Professor Elizabeth Newson who along with her colleagues, felt increasingly dissatisfied with the description of “atypical autism”, which was frequently used in the UK at that time (Christie et al., 2012). The National Autistic Society recognises PDA as part of the autism spectrum, but in some regions, PDA does not yet have formal diagnostic status, and this can lead to conflict between parents and professionals who may misdiagnose the child as disruptive or simply “bad behaved”. Many parents already dealing with the practical and emotional issues find themselves having to convince and “do battle” with the professionals who should be supporting them. For some, their experience can be especially harrowing if their child’s behaviour is seen as a reflection of their parenting skills (Christie et al 2012 p97).

“PDA is an anxiety driven need to control and avoid demands, therefore reducing anxiety whilst increasing indirect flexible approaches is more likely to achieve successful co-operation and wellbeing” (Network.autism.org.uk 2019).

The most recognised difficulty of individuals with PDA is an avoidance to engage with demands placed upon them by others and this could result in a range of excuses not to do a specific task. A person with PDA may attempt to talk incessantly or change a topic of conversation entirely in a bid to avoid a demand, and if this doesn’t work, the individual may become increasingly agitated until the behaviour finally spills over into anger, and in some cases, a full on melt down. However, people with PDA generally have much better social communication and interaction skills than other people on the spectrum, so can use those skills to disguise their resistance through common avoidance behaviour (Learn.autism.org.uk. 2019).

Features of PDA:

Compulsive resistance of demands may include –

- Constantly using excuses / complaining of physical impairments

- Changing the topic of conversation

- Withdrawal / Disengagement

- Refusal / Inability to Comply

- Panic / Meltdowns / Mood Swings

- Role Playing / Mimicking Behaviour

- In some instances people with PDA may not recognise social hierarchy

- Lack of Self Esteem / Confidence

Recognising PDA Behaviours:

Like many other people on the autism spectrum, people with PDA experience high anxiety levels and can feel that they are not in control. This leads people with PDA to avoid and refuse any requests that are made too assertively. Sometimes this is due to how the person with PDA interprets the question or instruction. This can lead them to avoid tasks and activities that they would otherwise enjoy, which can be upsetting for the person with PDA (Pdasociety.org.uk. 2019).

Like many other people on the autism spectrum, people with PDA experience high anxiety levels and can feel that they are not in control. This leads people with PDA to avoid and refuse any requests that are made too assertively. Sometimes this is due to how the person with PDA interprets the question or instruction. This can lead them to avoid tasks and activities that they would otherwise enjoy, which can be upsetting for the person with PDA (Pdasociety.org.uk. 2019).

Everyone has heard of the fight or flight response and these traits are particularly evident in people with PDA. When a person with PDA is given a task or instruction of some sort, this could result in an increase in anxiety. Dependent on the level of communication this could soon explode into a full-blown argument which could eventually turn violent with the person losing control entirely resulting in objects being thrown or lashing out (it at this point the person making the demands needs to back away and where possible give space).

– As children with PDA grow, so does their range of vocabulary and the ability to conjure even more “elaborate” excuses for not carrying out a request such as “my hands and feet don’t work”, and in most cases will eventually turn the conversation away.

– The flight response may see a child avoiding a demand by seeking out a change in surroundings, a quite space, or somewhere they feel safe. Remember, children need to feel safe and secure before they can function in an emotionally regulated way in any environment.

Diagnosis:

A diagnosis is the formal identification of PDA, usually by a professional such as a paediatrician, psychologist or psychiatrist. Recognition of PDA as a condition is fairly recent, and the apparent social abilities of many children with PDA may mask their problems. As a result, many children are not diagnosed until they are older (Limpsfieldgrange.co.uk. 2019). Over the years, people with PDA visiting medical professionals have been diagnosed with Borderline Personality disorder, Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder and High-Functioning Autism. This misdiagnosis mainly stems from the fact most medical professionals having very little information regarding PDA. It is extremely difficult to get a diagnosis of PDA due to lack of recognition in official diagnostic manuals and as stated by the pdaresource centre, “PDA does not appear in the diagnostic manuals published by the World Health Organisation or the American Psychiatric Association. In fact, it only just gets a footnote in an appendix of the guidance produced by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.”

Click HERE for the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO) training.

– Unlike Asperger’s and Autism, Pathological Demand Avoidance effects boys and girls equally –

Test Your Knowledge

– Take The Autism Quiz Here

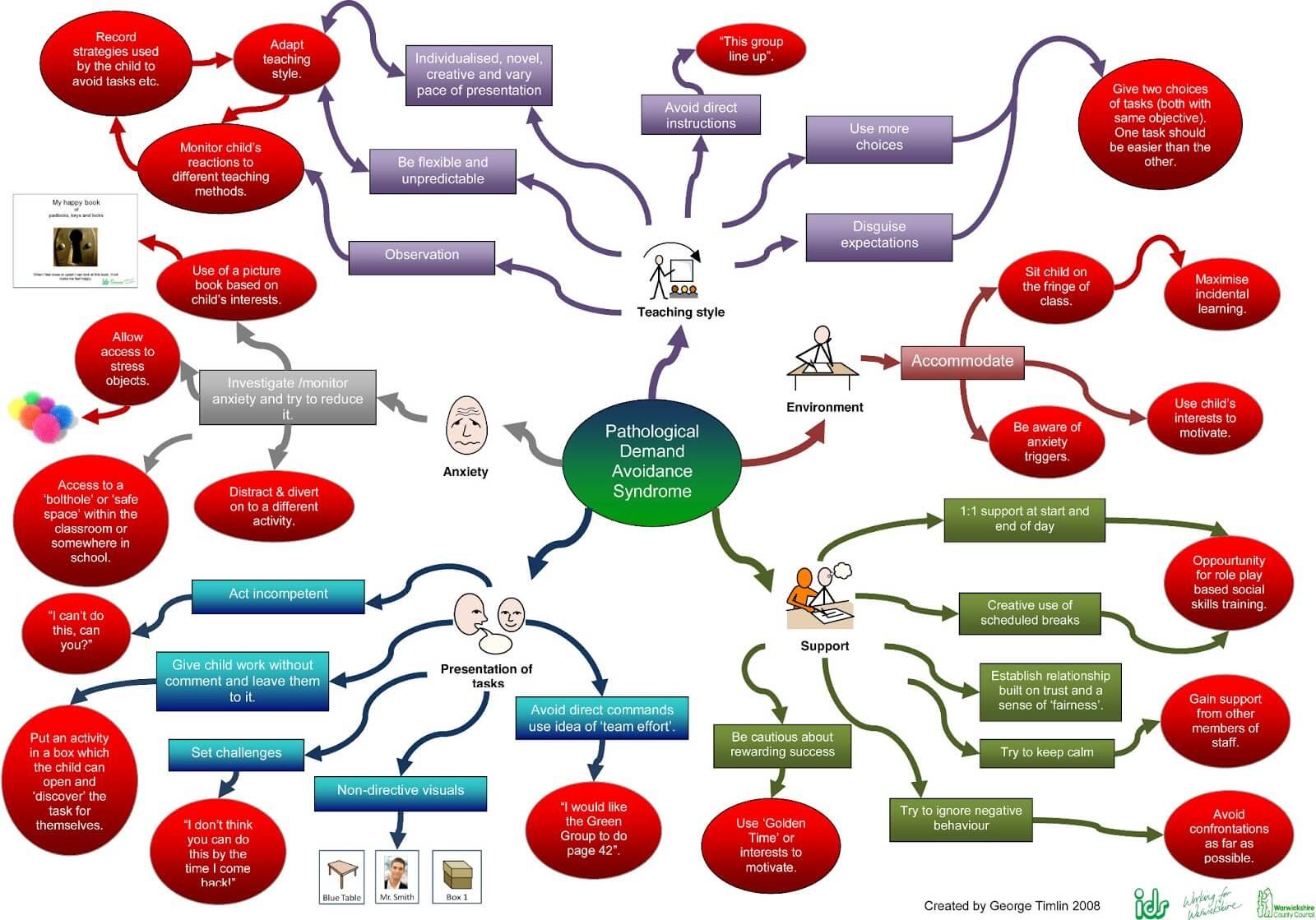

Strategies for supporting with PDA:

The first thing that any adult must remember when dealing with a child with PDA is that every interaction, or exchange, is a transactional (or two way) process. It isn’t enough for a teacher to look at the child’s behaviour and profile without first considering their own contribution to the situation. It may be a bit of a cliché, but if the adult isn’t part of the solution, they will become part of the problem (Christie etc).

– First of all, stay calm and DO NOT take on the child’s behaviour (anger will only make things worse). Some battles are won and lost in the first instant and how someone initially responds will have a huge effect on the outcome of any situation. There is a two-way outcome from any issue or situation that will affect the relationship between the adult and child: a negative or positive one. Turn everything into a positive because the more positive experiences we give to a child, the more positive feelings and behaviours will occur which will result in better reactions (Team Teach 2016). Try to go with the flow and don’t make a big deal when things go off course, be adaptable and relaxed when it comes to sudden change.

– Non-verbal communication make up 60% of how we communicate so think about body language, gestures and tone of voice. Eyes are one of the most powerful form of non_verbal communication but people with PDA may struggle with direct eye contact and as the average person finds more than 5 seconds intimidating the less time focusing on someone the better. Have a neutral face, a relaxed stance (do not cross arms or clench fists as a calm relaxed stance can go a long way in making someone feel safe) and remember your tone of voice can give words different meanings and change how they are received.

– Find alternative ways to give demands and be indirect with instructions, for example :– “Put your shoes on to play outside” may become “It’s good to put shoes on before playing in the mud”. Indirect instructions can also be disguised in fun stories such as “Do you think Luke Skywalker brushes his hair before going out?”

– Create indirect challenges such as: “I bet there isn’t anyone in the entire universe that can spell this word” but DO NOT make this a direct challenge, especially with siblings as this could create unwanted anxieties.

– Allow the person to take ownership of a demand, for example: “Put on your coat and get ready for school” can become “Now we have put on our coat and picked up our lunch, what do you think we should do now?”

– Use curiosity: If a child is anxious or upset, interject something different to raise curiosity levels (this is a great way to divert and distract) and gives a parent/carer time to think of an alternative strategy.

– Remember to always stay calm as getting angry with an extremely anxious person could lead to confrontation and may damage any relationships.

– One of my personal favourites is to try to use humour or if neccessary, a distraction.

– Learn to recognise the signs, identify triggers (write them down or keep a diary) and create strategies.

Support in Education:

For a child with PDA entering education, it is vitally important to have any/all interventions and support already in place, so an early diagnosis is crucial, not just for the child but also to assist staff in providing the best possible care. To help deal with anxiety, a safe and nurturing environment plays a significant role.

Not all anxieties result in the home, children with PDA are frequently unable to cope with everyday demands placed upon them in schools. Rita Jordan (Professor of Autism Studies, Birmingham University) states that child with a visual impairment would not be placed in a school without low vision aids and mobility training, yet a pupil on the autism spectrum is often expected to manage in school without these equivalent supports and be expected to be able to act and respond as other typical children”.

– In order to maintain attention in class, the staff may use a person’s interests to support learning. Just as Tom in the video shared his love of Star Wars and was allowed to play Star Wars bingo in Maths. Where possible, parents/carers should work together with school staff in order to create a structured curriculum that allows for learning but also gives consideration for moments of anxiety. Remember it’s not just about supporting the parents/carers, even the most skilled of teachers can fall at the first hurdle when working with a child with PDA if they don’t have a pre-planned strategy in place.

– We’ve already written about the importance of body language and how it can be used to build relationships and support anxieties, but a simple technique we practice in our own setting is one entitled ‘Mum/Dad on a park bench‘ – Now imagine if you will your at the park with your child, they’ve headed off in excitement to the nearest slide/swing and you’ve sat down for a quick five minute rest when suddenly you hear the words Mum/Dad and your child is desperately looking in your direction! What’s your immediate reaction? In most cases that child will see a positive response from their parent in the form of a smile, or possibly a thumbs up. With a simple gesture the child feels safe, they’ve received a positive response and will be actively encouraged to continue with what they were doing. – A deputy head teacher once told me that some autistic people view others as vending machines and each and every machine is unique. One vending machine may give a smile, whereas another may offer a hi five or deep pressure? The reason I mention this is there is an anonymous quote on a PDA Facebook support group that simply says “Don’t be a demand machine..”

– Along with first impressions and body language, you may wish to avoid giving a student demands on first entering the classroom such as please remove your coat or go hang your coat in the cloakroom. Yes these are behaviours that you want to happen each day, but maybe a visual or written instruction on the wall would be a good starting point.

– Building a relationship is HUGE and if you want a pupil to learn in a relaxed and anxious free environment, building a relationship is key. One excellent way of achieving this is by engaging with a mutual interest. As Miss Kelly in the video was aware, Tom was interested in Star Wars and Space. Not only did she use this information to formulate a maths lesson but also used Tom’s interest in space to introduce fascinating facts about the stars and grains of sand that even peers would find amazing. If the child has a favourite football team, collects Pokemon cards or follows a certain pop star then a teacher could help themselves considerably by learning just enough about this outside interest to create engagement in the classroom.

– Where possible identify a key worker / one to one support – Come together and develop a communication passport for the child, likes / dislikes / motivators etc.. and share with everyone who comes into the class.

– As mentioned above visual timetables are great for reducing demands – Additional processing time should be worked in to the child’s plan and implemented throughout the day.

– In my time working with children with additional needs, one of the most important lessons I’ve learned is to “leave your EGO at the door, DO NOT take things personally and DO NOT hold a grudge! Oh, and a little empathy goes a long way”.

>>>> Download a FREE Communication Passport HERE <<<<

>>>> Download A FREE Autism Wordsearch Puzzle HERE <<<<

Further Reading:

– Understanding Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome in Children: A Guide for Parents, Teachers and Other Professionals by Phil Christie, Margaret Duncan, Zara Healy and Ruth Fidler

– The Explosive Child by Ross W Greene, PH.D.

– Managing Meltdowns by Deborah Lipsky and Will Richards

– Raising a Sensory Smart Child by Lindsey Biel, M.A., OTR/L and Nancy Peske

– Can I tell you about Pathological Demand Avoidance syndrome?: A guide for friends, family and professionals by Ruth Fidler and Phil Christie

Useful Links:

– Diagnostic Pathway for Children

– Building a framework of strategies

– Education and Support in School

References:

Autism.org.uk. (2019). PDA (Pathological demand avoidance) – National Autistic Society . [online] Available at: https://www.autism.org.uk/about/what-is/pda.aspx [Accessed 17 Apr. 2019].

Learn.autism.org.uk. (2019). Pathological Demand Avoidance Conference 2018. [online] Available at: https://learn.autism.org.uk/ehome/pda-2018/home/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2019].

Network.autism.org.uk. (2019). Meeting the educational needs of pupils with PDA | Network Autism. [online] Available at: https://network.autism.org.uk/knowledge/insight-opinion/meeting-educational-needs-pupils-pda [Accessed 17 Apr. 2019].

Pdasociety.org.uk. (2019). PDA Society • Part of the Autism Spectrum. [online] Available at: https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2019].

Yates, E. (2019). Home. [online] Teamteach.co.uk. Available at: https://www.teamteach.co.uk/ [Accessed 23 Apr. 2019].